It’s Alive! And far more than what’s in print.

I admit that curriculum doesn’t seem like a thrilling or provocative topic for a blog! But every summer, districts commit inordinate amounts of time and resources writing and revising it. As I type, thousands of teachers and supervisors across the country are drafting millions of pages to prepare lesson guidelines for the new year.

It’s hard to imagine a professional educator being excited, engaged, or inquisitive sitting in front of a computer or at a conference table. In their minds and discussions, though, they are conceiving and creating something they hope will spark exactly those feelings in their students.

What’s “on paper”

You might think the curriculum plan tells us everything that will go on in classrooms, but what’s on the page isn’t always what gets taught.

And it turns out, not everyone even agrees what a curriculum is.

During most of my twelve years teaching high school science, I did summer curriculum work. My co-authors and I were tasked with writing the scope and sequence of our course content.

If we were lucky, about every 8 years we had a hand in choosing a new textbook. By June a copy was in our hands, and in July we were using a standard department form that laid out how to divide the text. For all practical purposes, the textbook was the curriculum.

(There was also a heck of a lot of recycling of the previous curriculum. One guy I taught with had cabinets full of dittos dating back over 15 years, though the curriculum had probably been rewritten or revised several times over that period.)

It didn’t take me long to understand that the curriculum is more than a syllabus, collection of unit lesson plans, piece of software, digital platform, or cabinet of papers. What we offer our students represents what we believe is important. It reflects our beliefs and values, reveals our assumptions, biases, and self image as an organization. Behind every decision is a mindset, and our curriculum expresses our point of view.

What gets taught

Today, most teachers and supervisors would say we had it backwards writing curriculum based on the text. Today we first decide what needs to be taught, then choose the best resources available to teach it. And how do we know what needs to be taught?

There are mandatory pieces to every curriculum. Each unit must align with current state learning standards and there are required topics that it must include, from the Bill of Rights to addiction. Additionally, it must address federal and state mandates (ex. the Amistad law), career prep, and course/level prerequisites.

There are mandatory pieces to every curriculum. Each unit must align with current state learning standards and there are required topics that it must include, from the Bill of Rights to addiction. Additionally, it must address federal and state mandates (ex. the Amistad law), career prep, and course/level prerequisites.

Even with requirements to be met and guidelines to be followed, educators are professional, trained, and independent thinkers. When writing curriculum, they add value by choosing worthy content and resources based on their experience and wisdom.

When they teach, they interpret the formal written curriculum by making decisions on strategies, pacing, leveling, and inclusion of current topics. In practice, they make the document come alive and personalized for each student.

All of what makes it into the lesson has been called the overt, received, explicit, or actual curriculum. But that’s not the only curriculum students actually experience.

Between the Lines

Academics have identified four to seven different kinds of curriculum, each with multiple names. Let’s focus on two that have the biggest influence and over which we have some control.

The Hidden Curriculum

Also known as the implicit or implied curriculum, the hidden curriculum is what students learn about school and the world based on how the organization functions and the adults working for it treat them.

For example, the amount of time spent on foreign nations in world history studies suggests the relative value or importance of each. When districts celebrate individual student scores on annual state tests, it tells students how much these numbers matter, and gives the impression that we prioritize tested subjects over non-tested ones.

When there are quantifiable inequities in our class placements and discipline, it makes students feel that success is based on who they are and not what they can do.

And when a hidden curriculum reflects a 19th century factory model, it values uniformity, obedience, and assimilation. A more evolved curriculum would actively nurture its opposite: creativity, expression, critical thinking, and independent decision making.

The Null Curriculum

What’s in a curriculum, whether overt or hidden, is complex enough. Students are also impacted by what gets left out. Not learning important facts and developing critical understandings can harm children, and our society, in the long run.

For example, curricula have historically not included works by diverse authors; the contributions of women, indigenous people, and people of color to U.S. history; mental health education; nor stories, ideas, and statements some would call critical of government, the establishment, or scientific progress.

How to keep the curriculum alive

Educators often talk about “the living curriculum.” More often than not, that simply means it gets updated periodically. As a former biology teacher, I’m going to run the phrase a few steps further.

Living things take in nutrients, are aware of and respond to their surroundings, maintain an internal balance, and function as an organic whole. Some might also say they have a purpose, or, at least, a role in their ecosystem.

If we treat our curriculum like a living organism, we will:

Feed it. Keep it fresh with new and diverse content and quality resources (for example, using tech simply as a non-tech substitute along with traditional methods and mindsets won’t nourish learning). And not just once a year or every three years. Effective teacher teams review how well the curriculum is surviving the test of teaching in every one of their professional learning community (PLC) meetings.

Feed it. Keep it fresh with new and diverse content and quality resources (for example, using tech simply as a non-tech substitute along with traditional methods and mindsets won’t nourish learning). And not just once a year or every three years. Effective teacher teams review how well the curriculum is surviving the test of teaching in every one of their professional learning community (PLC) meetings.- Make it responsive and adaptive. Organisms get stronger (or go extinct) through a push and pull with their environment. Challenge it, question it, doubt it. Regularly assess student success and interest and modify it with a mind to increase both. Adapt to multiple evolving standards, new career directions, and important social movements, discoveries, and knowledge. There must be room in a curriculum for change and growth.

- Keep it balanced. It isn’t easy to stay centered, but a healthy curriculum can meet disparate needs: between classical and modern knowledge; between fact and imagination; between depth and breadth; and between the desire for uniformity and comparability versus flexibility and personalization.

- See it in its entirety. Every curriculum should be multidisciplinary, each subject area informing the other. It should consider the whole child, not just attending to academic skills and knowledge– facets like personal experience, relationships, emotional health, and access to adult support. And we need to be aware of the many “kinds” of curriculum we’re teaching children.

- Make clear its purpose. Beyond college and career readiness, our mission is to graduate students who are kind, resilient, collaborative, creative, and ethical, among other traits. What evidence could you provide that your curriculum helps you meet your mission? Let’s also expose our hidden curricula and evaluate what’s been left out in our null curricula by looking at their impact on students.

All living things are part of a circle of life (cue Elton John here). If our purpose is to sustain our students and help them grow, we have to make sure our curriculum is healthy and nutrient-filled.

⚙ Dr. Marc

If you feel that someone in your professional network, neighborhood, the next classroom or cubicle would benefit from engaging in topics like the ones in these posts, I encourage you to forward them this email!

©2021 Marc Natanagara, Ed.D. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article and other resources available at authenticlearningllc.com

When duplicating this post in any form, please be sure to include the attribution in italics above.

When duplicating an infographic, be sure to include attributions within the graphic.

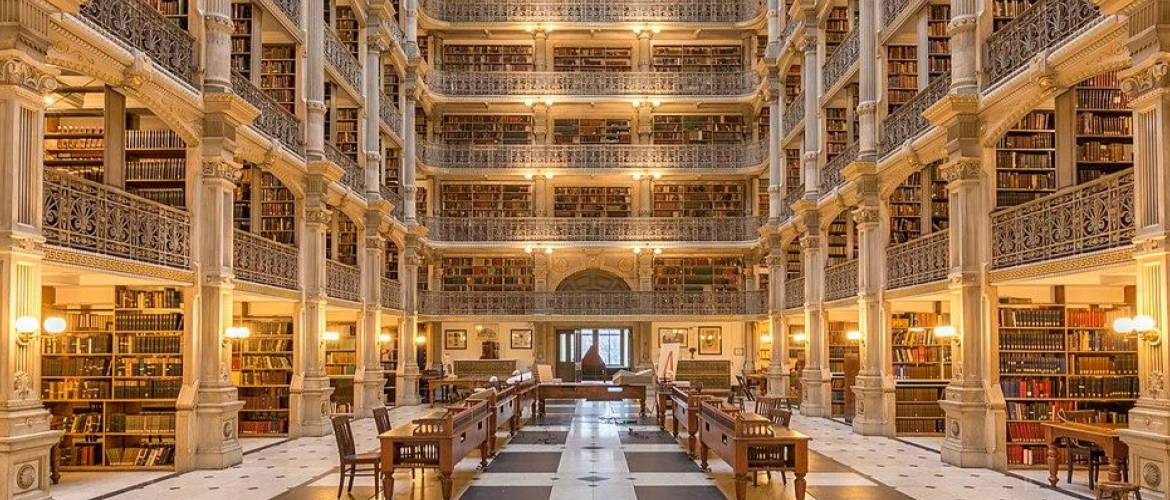

Image of George Peabody library by Patrick Gillespie, Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0 accessed from https://www.flickr.com/photos/40423570@N07/24513595561

Image of books from https://pixabay.com/photos/books-book-stack-books-pile-2547179 Free for commercial use, no attribution required.

Image of hamster by Dennis Blöte licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license, accessed from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mesocricetus_auratus_-pet_hamster-8a.jpg

August 2021