Poverty is the one factor most closely correlated with crime, unemployment, incarceration, and educational failure. So why aren’t we doing anything about it?

Two articles last week in The New York Times touched on the same question in roundabout ways:

“How can we help underserved kids become successful in the long run?”

The first article spotlighted a ten year old chess prodigy whose family lived in a New York City homeless shelter. The coverage helped GoFund a quarter of a million dollars for the young man’s family (most of which they donated to charity). At the end of the piece, the writer makes the following point:

“…Readers often want to help extraordinary individuals like Tani whom I write about, but we need to support all children — including those who aren’t chess prodigies. That requires policy as well as philanthropy, so let me note: President Biden’s proposed investments in children, such as child tax credits and universal pre-K, would revolutionize opportunity for all struggling children.”

That same day, I read several news stories covering Biden’s plan. One in The Times points out how decades of research have shown unimpressive long term results from early ed programs. A new study out of Boston, however, found small gains in graduation rates, college enrollment, and social-emotional indicators, though not test scores. (I discussed problems with such measures in a previous blog.)

Head start programs are likely well intentioned but miss the one factor every study shows has the greatest and most consistent influence on students’ educational success: wealth.

The impact of poverty on learning is no secret.

Recent data shows that 12.8 million children, or 18%, live in families experiencing poverty. An even larger percent are low income.

Poverty’s effects are like an inheritable disease with more long term and widespread impact on schools than COVID. Half as many impoverished students graduate high school as children of means and are five times as likely not to be employed or enrolled in secondary education. Dropouts are 3.5 times more likely to be arrested than high school graduates. Sixty-eight percent of all males in prison do not have a high school diploma.

And that’s just scratching the surface.* Poverty also hits children of color harder, one of several inequity multipliers worthy of their own discussion.

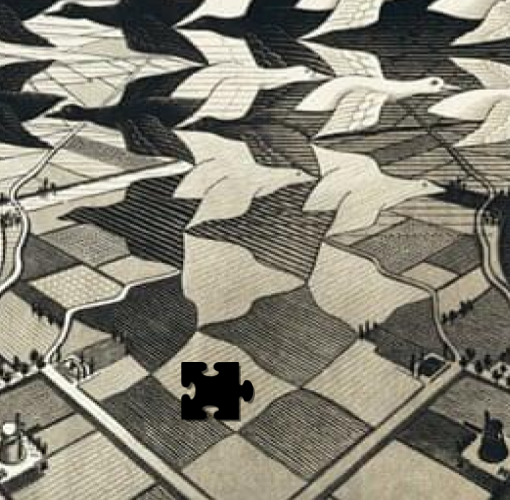

Let the circle be broken.

![]() The only chance the cycle of poverty stands of being dismantled is through changing policies, beliefs, and practices. Charities and social programs are tangents of that cycle that may actually perpetuate the same dogma that has trapped us where we’ve been for decades.

The only chance the cycle of poverty stands of being dismantled is through changing policies, beliefs, and practices. Charities and social programs are tangents of that cycle that may actually perpetuate the same dogma that has trapped us where we’ve been for decades.

Here’s an example of a cycle based on years of working with thousands of families. It is generalized and by no means describes everyone in need. Let’s start at the point in the cycle where parents are raising their first child.

- These parents did not experience success when they were in school. (Fewer than a third of parents in impoverished households finished high school.)

- They can access only low paying jobs, work hours that complicate raising a healthy family, and constantly experience the stress and difficulties of not having enough money.

- They not only have less time and less means to enrich their growing child’s education (ex. travel, summer camps), but they don’t have much confidence in the school system to help them. In fact, they may not even have the confidence or trust to push the system to work for their child.

- The child enters school behind their wealthier peers and with fewer supports. Problems that for other families may be common and manageable become magnified. Without extensive insight, advocacy, and action by the school system, the child has a high likelihood of not graduating or earning a livable wage– and all that comes with being underemployed.

- The cycle continues.

Of course there are families who avoid this fate. But the odds are stacked against them.

The thing about a cycle is that you can enter it– and break it– anywhere along its curve.

The more places you attack it, the more likely it is to be permanently disrupted. Poverty has no single cause and no simple answer. As with many critical and complex issues, that’s not a reasonable justification for doing nothing. Righting a pervasive wrong begins by asking, What can I do?

I’ve worked with several schools that are building cycles of success, the impact of which endures and grows over a lifetime– possibly more than negative cycles can. Positive cycles in schools are built on core understandings that pervade the entire district culture. Such organizations believe:

- When students are appropriately challenged and achieve, they build confidence and skills which promote future success;

- When they learn to trust their teachers and other adults like counselors, nurses, administrators, bus drivers, and custodians, they know where and when to go for support;

- When the content, language, assignments and assessments respect their experiences, points of view, and cultures, they feel welcome at the table and make deeper associations that endure;

- When students are connected to their community, they see schoolwork as relevant to real life, and both they and community members realize mutual value in each other.

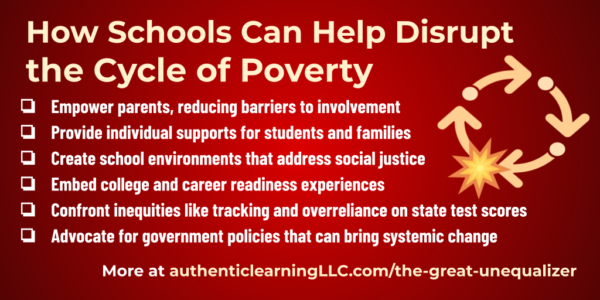

Schools with these beliefs are identifying and helping disrupt cycles of poverty at multiple entry points by:

- getting to know families more deeply and realistically; learning how to gain their trust, educate, and empower them; and eliminating barriers to involvement (e.g. offering translators, transportation, babysitting, after hours access)

- providing extra and individualized supports for both students and parents, from peer buddies to being a conduit for other social services to “two generation programs” that help parents find work

- creating classroom environments that eliminate classicism, prejudice, and pressure to conform to arbitrary and meaningless standards of wealth

- organizing experiences that make college and careers more accessible: tours, internships, shadowing, and job skills training (interviewing, resumes)

- rooting out inequities and injustices in the system (the “ bigotry of low expectations”) like tracking, underrepresentation in AP and STEM classes, overreliance on standardized test scores for placements, funding disparities, and de facto segregation

- becoming partners with communities and government to address poverty and advocate for systemic change through policies and social reform.

Spending billions on head starts can have a lasting positive impact, but early childhood programs alone are not going to get that elephant out of the room and back to the savanna.

Only when beliefs and actions like the ones I’ve shared above are in place in every classroom will students be far more likely to replace cycles of impossible struggle with cycles of success. Then not only they but their children will have a fighting chance to grow up in a system that works for them.

⚙ Dr. Marc

If you have a friend/colleague who speaks this kind of language, or whom you think would benefit from hearing it, please forward this post.

Fellow educators and their supporters can also get on the no-pressure mailing list to receive periodic newsletters/blogs and content like this post by using this link.

Cycling image CC BY-SA 3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:TachikawaKeirin.jpg

Broken cycle icon Kyle Barrett 2013

*Sources of data referred to in this article:

Annie E. Casey Foundation 2020

National Center for Education Statistics 2019

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center 2019

Stanford University Op-Ed: Schools vs Prisons 2014

PBS Frontline on Impact of HS Drop Outs 2012

©2021 Marc Natanagara, Ed.D. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article and other resources available at authenticlearningllc.com

When duplicating this post in any form, please make sure to include the attribution above.

May 2021