PBL nurtures our natural ability and desire to address real world challenges.

You could say that life is an endless series of problems to be solved. Thankfully, we’re perfectly equipped for it. From birth, we are driven to figure out how things work and to adapt them to our needs. Can’t stand up yet? Parents hid the cookies? When kids see a challenge, it’s “Bring it on.”

But when children see problems as too many or too difficult, or even not challenging enough, their interest in tackling the unknown can atrophy. These skills have to be reinforced and nurtured by teachers and parents through instruction, encouragement, support, and even letting them find their own way.

In schools we refer to acquiring these skills as problem-based learning, or PBL. PBL includes both processes and cognitive strategies that, with minor modifications, can be applied across many different kinds of challenges. It is a close cousin of the scientific method and the engineering design process.

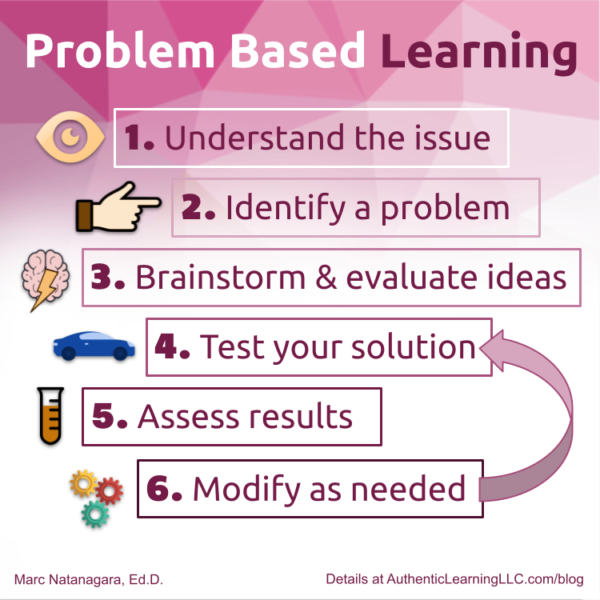

The PBL process varies slightly depending on its application, but typically embodies these stages:

Click here for a 2-page pdf with details and a classroom example

Here’s what that might look like (much simplified) for med students following these steps in a residency program:

- Students are presented information– x-rays, bloodwork, patient feedback– indicating the patient is experiencing abdominal pain (Step 1).

- On the basis of that evidence and their medical knowledge, they agree the problem may be a gastric condition (2).

- They propose a dietary solution (3), then test it through research, lab work, or advice to the patient (4).

- They then evaluate if the patient’s condition has improved (5).

- If not, they gather more information, then propose and assess changes to their recommendation (6).

Besides just solving problems, the PBL process and mindset includes and helps students develop these traits:

Critical thinking: conceptualizing and evaluating information in order to make informed decisions

Creativity: applying imagination and outside-the-box thinking

Empathy: being able to identify impact and put yourself in someone else’s shoes

Self awareness: e.g. an understanding of personal biases

Cognitive flexibility: open mindedness and a growth mindset

Collaboration: ability to work as part of a team and maximize complementary skills

Not coincidentally, industry leaders identify these same characteristics as essential to most careers. (EdWeek, March 2021)

Problem-based approaches have been used for centuries by archeologists, doctors, scientists, law enforcement, and many other professions. Clearly we like seeing problem solving in action. It seems like there’s a new TV series about these jobs, as well as “reality” competitions for cooks, makers, and survivalists, premiering every week!

It’s the problem, not the project

It’s worth differentiating problem-based from project-based learning. Much about these two practices can be the same, but I continue to see and promote two key differences in practice.

1) Not all projects are rigorous or engaging. A teacher has students construct a game instead of writing a book report. In place of worksheets, students are asked to build a model or diorama. These activities in themselves don’t rise very high on Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive processes. That’s especially true when students build projects following a model, template, or protocol. Following the process above hits all of them.

2) Students are capable of identifying problems. In the above examples, the projects are primarily an alternate means of presentation. Sometimes they are used to model a solution, but even then, the problem is usually defined by the teacher (or the curriculum they purchased). Students are very capable of identifying and defining problems. We underestimate them when we don’t let them, and they miss the opportunity to practice a foundational element of problem based learning.

In short, simply doing a project is no guarantee learning is being reinforced. On the basis of these commonly found issues, I avoid the term project-based.

“I have acquired a very particular set of skills.”

— Liam Neeson in Taken

There’s more to solving problems than just skills.

Though problem solving can involve some risk taking, unlike in movies, you probably won’t get hurt doing it.

Liam had good reason for applying those skills: his kidnapped daughter. That’s also true for real people; if a problem means nothing to us, we’re unlikely to be motivated to solve it.

Think about that squirrel. Her acorn-sized brain seems to hold an infinite number of tricks to get into any bird feeder. But what makes her so relentless? Survival, naturally. Likewise, children may learn a skill set, but finding motivation is just as important.

We find reasons to be motivated when a problem is authentic to us. The issues children are asked to confront should have both real world and personal meaning. Solving it should address an issue that doesn’t have a single solution and that can help others. When that happens, motivation becomes intrinsic and independent of rewards. That’s another reason why step 2 in the PBL process (above) is essential.

Adults nurture this process by asking children interesting questions and giving them the freedom to ask and explore questions of their own. We can model how we use a process for finding solutions to difficult problems we routinely face. And we can show them how trial, error, frustration, and perseverance are part of a happy and productive life.

In classrooms, we can ask students more open ended questions, and ask ourselves, “Why DO they need to learn this?” We can take our existing content and skills and shape it around problem-based scenarios that have meaning to our students.

Children who practice these skills develop an inner voice that supports them when confronted with a novel problem. It says, “I’ve dealt with many different kinds of problems. I haven’t seen this particular one, but I know how to deal with it.”

As a parent, I wish I weren’t leaving my three kids a world filled with so many problems. But I am betting on the skills and passions they’ve developed to address them– probably better than my own generation has– for their own good as well as for the world.

⚙ Dr. Marc

If you think someone in your professional learning network, neighborhood, or the next cubicle would benefit from engaging in topics like the ones in these blogs, please feel free to forward this post to them.

©2021 Marc Natanagara, Ed.D. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article and other resources available at authenticlearningllc.com

When duplicating this post in any form, please be sure to include the attribution in italics above.

When duplicating an infographic, be sure to include attributions within the graphic.

A more detailed comparison between problem- and project-based learning was explored in an article I wrote in 2016, published here, and in a presentation at the 2017 World Maker Faire.

Squirrel photo Wikimedia Creative Commons 2.0 Generic