Active learning teaches children to teach themselves, ultimately becoming independent learners.

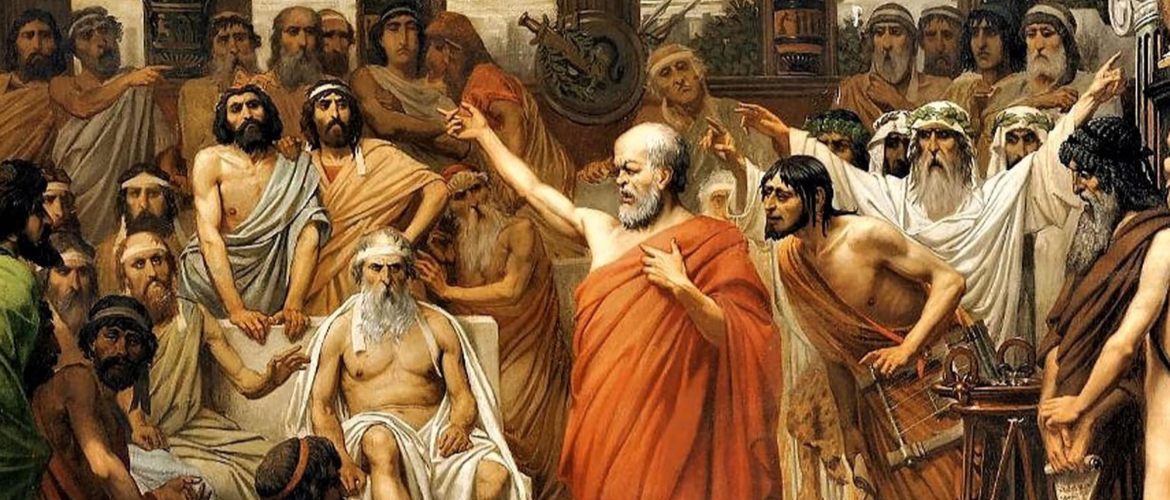

As with many influential historical figures, the Greek philosopher Socrates was “underappreciated” in his time by the powers that be. It wasn’t just his unkempt appearance and rabble rousing. His instructional method of argumentative dialogue led hundreds of followers to become skeptics of the status quo. And if there’s anything authorities hate, it’s questioning authority.

Things did not turn out well for the father of western philosophy.

Fast forward sixteen centuries. Teaching young people to question and through questioning are now cornerstones of both an effective education and an informed society. Socratic discussions, along with activities like debates, role plays, brainstorming, and investigations are examples of active learning.

An active learning approach teaches students to develop understanding through open-ended problems, inquiry, exploration, and peer interactions. It engages higher order thinking like processes like analysis, evaluation, and creation (a la Bloom’s taxonomy).

When we are successful, we haven’t just given students better access to content, we’ve taught them skills for life, like:

- critical thinking (assessing factual evidence to develop unbiased judgments)

- executive function ( goal setting, managing work and emotions)

- metacognition (understanding how and why we think what we do)

Such skills practiced and attained through active learning are transferable across space, time, and discipline.

In the big picture, how students learn to learn is more important than the specific content.

It is no easy task to create active learning scenarios, for either a teacher or parent. It’s not so easy for kids, either. Look again at the painting of Socrates. The artist depicted his adherents as looking either disturbed, lost, or riled up. That sums up pretty well what can happen when you put students more in charge of their own education!

“What the educator does in teaching is to make it possible

for the students to become themselves.”

Paolo Friere

I am happy to say that over the past decade or two, active learning has replaced straight-on lecturing in most K-12 classrooms most of the time. (A colleague once joked with me that lecturing was good preparation for first year classes in college, but, of course, that’s not a good reason to still do it.)

Getting students to direct their own learning can begin as simply as think-pair-share. Once they get better at it, they can engage in case studies, peer teaching, and group challenges. This chart from the University of Minnesota places a few dozen familiar classroom strategies on a spectrum of “activeness.”

What active learning looks like

My brother and I were often subject to active learning in our home. When we were very young, our mom went back to college to get her degree and certification to work in public schools. She would regularly “test” education theory from her classes on us. She’d praise us for the process rather than for the product, ask questions instead of providing answers. It could be maddening, but after having and working with kids, I understood why her choices were important for our intellectual and emotional development.

I remember one of my high school students asking, “If sound needs a medium to move through, how can light move through the vacuum of space?” “Great question!” I replied. “Why do you think?” Though not initially amused by my Socratic diversion, in the (pre-internet) class discussion that ensued, we came up with several ideas which we returned to as we learned more. (The nature of light, by the way, is still a matter of great scientific curiosity.)

During a chemistry unit, I asked students to jot or sketch info on common elements onto index cards. I then tasked them in groups with organizing the cards in any way that made sense to them. The result was a personalized periodic table. The rationale they provided for their table showed what they understood about atoms. The process showed them why the table is organized as it is (and why that needn’t be the only way).

I also earned my teaching certificate through an active learning model. As a science major, I had to attend evening “alternate route” classes for the first year and a half on the job. Rather than lecturing us on education theory, Professor Gribbin had us discuss our problems and frustrations from our day of teaching. In small groups, we’d work out the issues and apply educational strategies to address and test them. (This also made our work authentic.)

During the pandemic, students who were familiar with learning actively had an easier time working independently. They knew better how to ask questions, access resources, work in teams, and address problems when they arose. For example, some teachers had students engage with content and resources “offline” (videos, simulations, readings, podcasts, tutorials, animations, etc.) and spent live class time applying and exploring gaps in their understanding. Those are important lessons moving forward, whether schools continue with some form of virtual learning or not (see Edweek 12/16/20).

The efficacy of these practices isn’t just teacher intuitive, feel good stuff. Research continues to show that students achieve more through this model (see Freeman et al, 2014 and Michael, 2006). Even college students may not realize it, though. An experiment at Harvard in 2019 showed that students believed they had learned better in a lecture setting, which was demonstrably false. (Read this summary article and consider why!)

When I think about developing habits of mind, I always go back to what children are like at the age when they first come to school. They are curious, want to be active and involved, and enjoy learning new things, even if just to please an adult. Teachers and parents won’t be guiding them forever.

Both unconditional love and nurturing an excitement for learning represent the best we can give them. These are two gifts that keep on giving and that they can pass on to their kids. My parents and teachers provided it for me, and I hope to continue paying it forward.

⚙ Dr. Marc

If you feel that someone in your professional network, neighborhood, the next classroom or cubicle would benefit from engaging in topics like the ones in these posts, I encourage you to forward them this email.

Socrates’ Address painting by Louis Joseph Lebrun (1867), from the public domain

Image of Periodic Table by litherland/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 from the International Science Council webpage

When duplicating this post in any form, please be sure to include the following attribution:

©2021 Marc Natanagara, Ed.D. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article and other resources available at authenticlearningllc.com

When duplicating an infographic, be sure to include attributions within the graphic.

April 2021