More than curriculum, children must be at the forefront of technology decision-making.

Is tech being used to meet the lesson’s needs or our students’ needs?

Folks outside the education profession may wonder how big decisions get made. With technology especially, which can be untested, costly, and quickly obsolete, I ask myself this question all the time.

That’s not to say that school decision makers don’t investigate options thoroughly or that they’re usually wrong. Most tech gets the job done, to some degree. But since research supporting the effectiveness of tech use is scarce, we’ve had to look elsewhere for guidance.

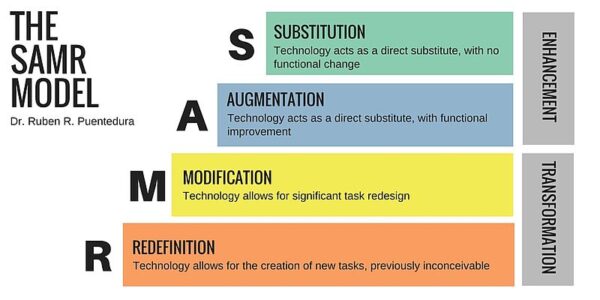

Most ed tech users have heard of SAMR, TPACK, or LoTI. These models help practitioners evaluate the quality of and reasons for tech use in their lessons. The baseline level in each model is using tech as a substitute for an existing practice, like drawing a polygon in a computer program instead of on paper. At its highest is a lesson that would be unlikely without tech, like a virtual field trip– handy during a pandemic or if you want to go someplace out of district, like Mars.

Those who talk about “technology integration” are likely operating at that introductory level. With technology so much a part of our lives and with so much potential to advance learning, talking about integrating technology into our lessons is like talking about integrating pencils into our writing. It’s not about the pencil; it’s about the writing.

Image from Wikimedia Commons

Starting a lesson plan thinking about how to use a resource or what resource to use, though, is putting the cart before the horse. The first question to ask is Why? What is the purpose of the lesson and why is this resource best suited to make it happen? The most fundamental answer is, “To meet student needs.” But is that too much to ask of technology?

Need fulfillment motivates everything we do

At some point we all learned about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. By the 1970s, Maslow had expanded it from five to eight levels. It is now also understood that while lower level needs usually must be met in order to address higher level needs, they needn’t be exactly in order nor completely satisfied. (A common sense example is finding plenty of love and friendship among populations lacking basic necessities.)

Maslow did not create the hierarchy specifically for schools, but it’s part of every curriculum. Woven within every subject matter is guiding students to find a better sense of security, dignity, self esteem, independence, and fulfillment.

I often think of Maslow’s view of human motivation when making decisions intended to help students meet their potential. And because of my love-hate relationship with tech and how it’s used, I have found it productive to apply it there. A hierarchy of needs can help us “keep our eye on the why.”

After years of trying different technologies and working with thousands of educators and people in industry, I realize it’s less about the specific tool than what a teacher does with it, but I wanted to see how far we could go. Taking a needs-based approach, we used an version of the hierarchy to pair great pedagogy with the right tech tools. Below is the general approach. An example follows.

Educators often instinctively focus on the first two levels. When I ask, “Why should we use this technology?” I frequently get a response equivalent to, “Because kids like it,” which is not a bad start. We know our students are practically born with technology in their hands. But once we’ve found something that gets their attention, now that we’ve opened that metaphorical door and they’ve stepped in, then what?

Addressing lower level needs is a gateway. After establishing student interest and comfort, we’ve got them where we want them– ready to dive into subject matter, access different parts of their brains, look for connections, meaning, and even joy.

Instead of having students create PowerPoint reports and 3D print keychains, we can find and use technology that sparks curiosity, creativity, and caring.

Let’s take a unit based on Macbeth as an example. (If you think this is only a secondary level scenario, check out what Marva Collins accomplished with elementary students for 40 years.)

Back in the 1980s, my high school English teacher, Ilene Skolnik, instilled a passion for Shakespeare in 25 seniors with varying levels of motivation. We dissected the bard’s use of language, memorized and acted out scenes, went to NYC to see it live on stage, and drew connections to current issues.

Mrs. Skolnik was a joyous combination of master teaching, enthusiasm, and a love for her subject and her students. Her class met many of my needs and I emerged more knowledgeable and confident.

Let me point out that this was well before the internet or personal computers. Clearly no such tools are necessary for a great lesson! However, now having practically infinite resources at hand (many free), what more could we do?

Pick the right tech and use it with a focus on student needs

Here are some examples of ways to teach Macbeth using today’s tech to spark student interest and facilitated deeper understanding.

1 and 2. Physiological and safety needs could be addressed within an educational game environment. (I’ve expanded these levels to include fundamental social-emotional-psychological needs– a healthy body and mind being inextricably linked). Minecraft, for example, is stimulating, open ended, and accessible. Using it to model the Globe theatre could help students understand the challenges of performing in a “theatre-in-the-round.” It’s also safe (level 2). Keep that in mind with all technologies. Students should not have to worry about their privacy, online bullying, or inability to access resources.

3. The need for friendship and belonging can be met through collaborative digital spaces (Zoom, Meet, Padlet) and the judicious use of social media, particularly vital when students are distance learning. They could learn lines and use a video platform like Tik Tok to record a scene from Macbeth using 11th century backgrounds. The important paradigm here is working together, with each making a needed contribution.

4. Recall that esteem needs are both how we view ourselves and how we wish others to view us. Esteem comes from real and meaningful accomplishments. Much more than in the 1980s, students can now easily cross-compare the text with resources like video clips, research, news media, and historical explorations to gain a better understanding, which creates confidence. Final projects and other portfolio-worthy work can be shared both with classmates and the larger community. Google Classroom is a safe space for peers and the Hewlett Foundation’s Share Your Learning offers more global avenues.

5. Students’ cognitive needs can be targeted through learning new skills that require new ways of thinking. Coding hits that mark (with potential future career benefits!). Students can identify plot points in the play and create a Micro:bit program using block coding, Python, or Java that randomly drops “prophecies” like the three witches. Peers who make and heed the connection between these rhyming warnings with the actions in the play, unlike Macbeth, may be able to avoid his fate.

6. Technology opens up worlds of creativity to address aesthetic needs. (Educators will also recall that creation is the highest level of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives.) Students could use Canva or ExplainEverything to create a digital print or video promotion for a performance of the play, or record a podcast debate between two characters (like Macduff and Macbeth) over a plot twist.

7. It would be a stretch to suggest that technology can directly lead to self actualization. But helping students on a pathway with that goal in mind, they can use personalized online courses, tutorials, mentors, and social groups to expand their understanding of Shakespeare, classic tragedies, leadership, Scottish history, etc. Give them the confidence and freedom to explore gaps in their learning and pursue personal interests.

8. Transcendence is also a lofty goal for K-12 education. We can point them in that direction by guiding them to relate Macbeth’s themes to the real world. With tech resources, they can actually plan to address them. Macbeth and Lady Macbeth’s ambition lead to a spiral of violence that is sadly not unfamiliar in modern times. Students can learn more about social justice through the UN Sustainable Development Goals, Amnesty International, the Center for Anti-Violence Education, or Human Rights Watch. They can develop a plan to reduce violence, on whatever scale they choose, including a social media campaign (actual or simulated).

I’ve seen a teacher turn an Excel spreadsheet into an active, challenging, and engaging lesson. And I’ve seen hours wasted with students passively wandering through augmented reality. There are myriad other examples for us to hone our understanding of which combination of tech and strategies work and which don’t.

No one would say technology is the solution to all our problems (well, maybe Elon Musk). But I’ve experienced how it can help students feel safe, challenged, confident, creative, and on a path towards self fulfillment. The difference is between focusing on the technology and focusing on student needs.

⚙ Dr. Marc

If you have a friend or colleague who speaks this kind of language, or would benefit from hearing it, feel free to forward this post.

©2021 Marc Natanagara, Ed.D. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article and other resources available at authenticlearningllc.com

All are welcome to share and use the contents of this and any public post. If duplicating this post in any form, please make sure to include the attribution in italics above. If duplicating any infographic in the post, be sure to include the attributions within the graphic.

Focusing on student needs (using a version of Maslow’s original five level hierarchy) and technology has been a topic of my staff meetings and workshops since I became a district administrator in 2012. I explored it as part of an article written in 2016 and published in the March 2017 School Leader magazine.

Temple image Karisa Studdard CC0 Public Domain Free for commercial use. No attribution required.