Mirror, Mirror

One of the best suggestions I’ve received in the past few years was from professional coach Katherine Golub. She advised me to “pause” whenever my thoughts were approaching capacity. (It happens a lot when I’m in the car. Talk about distracted driving!)

I used to believe that if I weren’t juggling responsibilities constantly, I couldn’t be as good as I envision myself. I’ve come to realize that clearing head space on a regular basis is more productive– and saner. Now I’m in the habit of pausing and reflecting even before I’ve reached critical mass.

You probably know someone who seems to “never learn.” Maybe it’s you who feels as if the same mistakes happen over and over. Or maybe you’ve plateaued in some aspect of your life or work. I believe reflective practice is what keeps me growing and has led to many of the accomplishments with which I am most satisfied.

What is reflective practice?

Reflective practice is a cycle of assessment and action. It is an iterative and systematic review process of continual questioning, validation, filtering, and prioritizing. It’s mostly about change.

Reflection often begins by asking, “What just happened?” Then when we dig below that surface, we identify what points of view were operating and what beliefs are behind them. This form of introspection challenges both our personal preconceptions and the status quo. And it helps us focus on the why at least as much as the how.

It’s said that experience is the best teacher, but experience alone is not enough, and reflection is more than just looking in a mirror. It’s about action. It’s an internal evaluation system, the goal of which is to provide a solid basis for making better decisions.

It’s said that experience is the best teacher, but experience alone is not enough, and reflection is more than just looking in a mirror. It’s about action. It’s an internal evaluation system, the goal of which is to provide a solid basis for making better decisions.

Why don’t we reflect more often?

We observe and reflect all the time. After a lesson, teachers almost reflexively note which students weren’t “on,” how well a new resource worked (or didn’t), and where they should put activity materials next time to create less chaos. What doesn’t come as naturally is doing it deliberately and purposefully, what is often called critical reflection.

We may be resistant to critical reflection because we believe it is:

- Not a priority. We allocate time based on perceived value. If, as a busy person, I don’t believe the impact of reflection can be a game changer, it surely won’t make my daily to-do list.

- Unfamiliar. If it doesn’t come naturally, is not taught in college nor part of my professional learning plan, all I’m left with is the fear of the unknown. Why not stick with what I know?

- Scary. The word “critical” is right in the name! Even if it’s a constructive critique of my practices, what if I (or, worse, others) find out I’m not doing what’s the “absolute best” for my kids?

- More work. When I’m done with a lesson, I’m DONE. (Which may be how students feel when we ask them to review and revise their work!) Besides, I already reflect unconsciously. Why take on more? In fact, I sometimes find, if I think too much, I get “analysis paralysis.”

- Squishy: Asking “what happened” includes thinking about feelings– mine and my students’. If I am one who sees teaching as more science than art, going there would be a stretch.

Hold tight! Reflection is for both scientists and artists. There is a system, it will make an impact and become a priority, you are able to learn to do it without fear, your work can become more effective and efficient (aka easier), and your feelings will thank you.

“A person who reflects throughout his or her practice is not just looking back on past actions and events, but is taking a conscious look at emotions, experiences, actions, and responses, and using that information to add to his or her existing knowledge base and reach a higher level of understanding.” (Mathew, 2017, p. 127)

How is reflective practice valuable?

Self knowledge builds confidence and assuredness. Research shows that reflection can specifically help us…

- develop metacognitive (thinking about thinking) skills to gain new insights on self and work (Kuiper, 2004)

- identify strengths and weaknesses in practice, then learn to problem solve (Isaksen, 2004)

- use student and peer feedback to reduce barriers to learning and develop better adapted lessons and strategies, with less randomness and disconnection (Hattie, 2009)

- examine underlying biases and beliefs, which can lead to points of view better suited to the situation (Brookfield, 2017)

- bridge theory, philosophy, beliefs and practice (Mathew, 2017)

- appreciate our individual and communal skills, knowledge, creativity, and adaptability to become more collaborative and autonomous, deliberate lifelong learners (Sempowicz, 2012)

What does effective reflection look like in action?

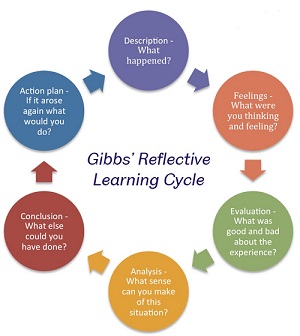

Reflection is an active and continuous process. Building on Kolb’s (1984) learning cycle, Gibbs (1998) proposed a reflective learning cycle, made up of six actions:

Description– Objectively, what happened?

Feelings– How did you/students feel before, during and after?

Evaluation– What worked and what didn’t? Who made it so?

Analysis– Why did (specific) processes and outcomes work as they did? What helped or hindered? What biases, dispositions, beliefs, or habits might I have that impacted the result?

Conclusion– What could be done differently or should be replicated next time?

Action plan– What do I need to do to improve the situation? What additional information, skills, or habits would help?

Steps to Develop the Skills and Habits of Reflection

Habits and skills are made and honed through practice. Here are some steps to get started:

- Set a clear schedule for reflection and commit to it. After teaching seems ideal but not if you’re wiped out or thinking about the next thing. When you start planning the next lesson might be an appropriate time, or you could build it into the class period, having students reflect on their work while you reflect on yours.

- Make reflection concrete and explicit by capturing it in words, numbers, or images. You can use journaling, lesson plan addenda, blogs, collegial discussions, social media. threads, notes apps, voice memos, videos, portfolios, peer and supervisor observations, inventories, checklists, and other self assessments.

- Streamline data collection in ways that make it seamless to analyze the impact of your actions.

- In addition to your experience as the teacher/leader, consider student points of view on the same activity. Intentionally solicit their feedback.

- In its fullest realization, critical reflection involves other people’s insights and sparks collaboration. Turn PD days, team meetings, and mentorships into peer reflective groups, where ideas and results are shared. More participants in reflective practice means more perspectives and more useful data.

Most importantly, reflect in ways that make sense to you. Like a workable diet, choose a way that you can keep at it.

Reflective Practice is Worth the Investment

As John Dewey said over a century ago, learning is experience plus reflection. With a regular influx of new students, new content, new skills, new mandates, and changes in society and our own lives, success in the classroom often feels like a moving target. Critical reflection helps make sense of it all by helping us more clearly see what’s happened and define our role in it. It allows us to safely experiment, then consciously and explicitly examine and assess our choices so they get better and easier with practice.

Developing the habit of reflecting without judgment or blame can refresh and de-stress our work. Acting on what we discover will help us, and our students and children, continue to grow and renew.

⚙ Dr. Marc

If you feel that someone in your professional or personal network would benefit from reading and engaging in topics like this, please forward them this email. I only ever use email contacts to provide information such as this post, and will never share contacts with any other person or organization.

©2022 Marc Natanagara, Ed.D. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Articles, services, and other resources accessible at authenticlearningllc.com

When duplicating this post in any form, please be sure to include the attribution in italics above.

When duplicating an infographic, be sure to include any attributions within the graphic.

March 2022

Images

Photo of Mount Rainier from https://www.nps.gov/mora/index.htm in the public domain

Image of John Dewey in the public domain

References

Brookfield, S. (2017). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team. Getting started with reflective practice. Cambridge Assessment International Organization. https://www.cambridge-community.org.uk/professional-development/gswrp/index.html

Dewey, J. (1910). How we think. New York: D.C. Heath & Co. Full text accessible via Project Gutenberg

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. London: Further Education Unit.

Hattie, J.A. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Isaksen, S.G., & Treffinger, D.J. (2004). Celebrating 50 years of reflective practice: Versions of creative problem solving. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 38(2), 75–101

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kuiper, A.K., & Pesut, D.J. (2004). Promoting cognitive and metacognitive reflective reasoning skills in nursing practice: self-regulated learning theory. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 45(4), 381–391

Mathew, P. (2017). Reflective practices: A means to teacher development. Asia Pacific Journal of Contemporary Education and Communication Technology, 3(1), 126-131.

Sempowicz, T., & Hudson, P. (2012). Mentoring preservice teachers’ reflective practices to produce teaching outcomes. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 10(2), 52-64.

2 thoughts on “Reflect to Improve both Learning and Living”

I agree, but kids are not taught this in school. Yes teachers analyze their work, but students are randomly given a problem to solve as a team and then made to analyze their solution. This homeschooling enrichment program makes kids problem solve by making them come up with a solution to get members from point a to b in the rain without getting wet. Kids have to learn teamwork, problem solving, reflecting and adjusting while developing solution. Talk about real world application. More of this hands on application needs to be provided in the school system.

Erika, you are so right that we don’t often teach students to reflect. My research (and experience) also show that. I’ll post that piece in the near future.

As for PBL, you know and others can see from my writings that this is a big issue for me! I have advocated for problem solving strategies that are more authentic as an admin in TR schools and in my work with other districts. In fact, I believe rather than assigning adult-generated and random problems like getting wet in the rain having students identify problems to address. Then they not only have real world meaning, but personal meaning.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts!